Today's society asks not only for specialists but also for builders of humanity, servants of the community

Today's society asks not only for specialists but also for builders of humanity, servants of the community

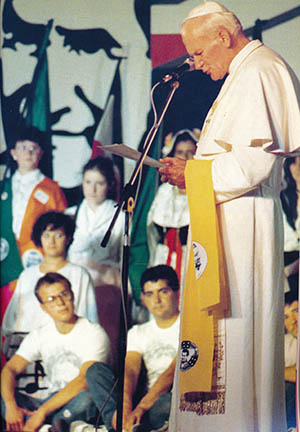

In the evening of Saturday, 3 September, the Holy Father went to the University of Turin, founded in 1404, where he addressed representatives of the "World of Culture” in the inner courtyard of the main building as follows

Dear Rector Magnificus,

Dear Deans of Faculties and Academic Staff,

Dear Students and Collaborators,

I am happy and grateful for this opportunity to meet the Academic Corps, the students and the auxiliary personnel of the State University of Turin which, rooted in a great historical tradition - along with the Polytechnic, rightly appreciated for the wealth of scientific results it has achieved - has a well-deserved prestige within the Italian and international scientific communities.

I greet and thank the Rector Magnificus of the University Prof. Mario Umberto Dianzani, for his gracious greeting, in which I discerned not only the expression of sincere deference for my person, but also the witness of a commitment to the search for truth with respect for the conscience of each individual, and the lofty sense of responsibility which animates academic authorities and staff in their daily educational tasks.

I likewise greet the students who, through their representatives, have expressed the problems, which assail them, along with the aspirations and the endeavor to excel by their own efforts, so typical of young people who are free and open to the infinite. Young people are the prime "targets" of the university institution, which, from its very origins, has placed them at the centre of its interest and zealous activity. To them I give a special, affectionate greeting, with the joy that I always find in meeting them and sharing their problems, concerns and aspirations.

The university community

The university was conceived as a particular "community” from the beginnings of this institution in the Middle Ages. A community of professors/men of science and students: the two components were then closely united to one another, so that the university/community, as a body composed of intimately united parts, had a regimen of mutual participation and self-government in which the teachers felt responsible for the formation of the students, and the latter, thus involved in rigorous academic requirements, were directly involved in the life of the university.

This was the character of the institution from its very beginning - and it is the same today. Indeed, in the current phase of great sensitivity to social living and its possibilities for communion, the aim is to re-discover the inner dynamism of the university community. The university, therefore, must truly be, in our day also, a community of persons which unites academic authorities, the various levels of teachers, students, administrators, auxiliary personnel and all those who participate directly in the life of the university, in order to avoid the university's being-reduced to a business concern which ignores relations with its clients. On the contrary, all the members of the university community will endeavor, in a spirit of participation and co-responsibility, to make the institution more united, creative, and truly concerned with the common good.

All this refers also to the University of Turin. It began in 1404 with the institution of a Studium generale "for the teaching of theology, canon and civil law and of every other customary faculty" [Cf. The document of institution November, 27 1404, in T, Vallauri. Storia delle Università degli Studi del Piemonte, Torino 1845, I, pp. 239-241]. It was always intimately linked to the history of this city and region, thus emphasizing a fruitful relationship between the ancient Athenaeum which promoted and developed the various fields of human knowledge and the life of the people, within the fabric of historical, political and cultural events, and in the uninterrupted effort of integration of Church and society, for the good of the human person and his cultural, moral, spiritual and civil growth.

The tasks which the university is called to undertake, today as in the past, in the field of knowledge and teaching, concern the difficult synthesis of the universality of knowledge and the necessity of specialization. As the Second Vatican Council observed. "Today it is more difficult than ever for a synthesis to be formed of the various branches of knowledge and the arts. For while the mass and the diversity of cultural factors are increasing, there Is a decline in the individual persons ability to grasp and unify these elements. Thus the ideal of 'the universal man' is disappearing more and more” (Gaudium et Spes, 61). Now, it is precisely characteristic of the university, which is antonomastically universitas studiorum as distinct from other centres of study and research, to cultivate a universal knowledge in the sense that in it every branch of knowledge must be cultivated in a spirit of universality, that is, with the awareness that each one, although diverse, is so linked to all the others that it is not possible to teach it outside the context, at least intentional, of ail the others. To withdraw into oneself is to condemn oneself, sooner or later, to sterility and to risk exchanging the norm of total truth for a keener method of analyzing and grasping a particular section of reality (cf. Discourse at the University of Bologna, 1982, April 18). The university therefore must become a place for meeting and spiritual collating in humility and courage where people who love learning can learn to respect, consult and communicate with one another, in an interweaving of open and complementary knowledge with the goal of leading the student towards the unity of the knowable, that is, towards the truth which is sought and safeguarded beyond any manipulation.

In this light we also find the answer to the problem of the autonomy of the university institutions, that is, of freedom of research and that of the limits of science in respect for the human vocation. In this regard I deem it my duty to reaffirm that "freedom has always been an essential condition for the development of a science which preserves its innermost dignity of the search for truth and is not reduced to a mere function, used as an instrument of an ideology, for the exclusive satisfaction of immediate ends, of material social needs or economic interests, of perspectives of human knowledge inspired solely by unilateral or partial criteria typical of biased, and for that very reason incomplete, interpretations of reality" (ibidem).

At the same time it is necessary to focus on a field of action that is no less important and crucial: the university institution must serve the education of the person. The presence of even the most prestigious cultural means and instruments would be worthless if they are not accompanied by a clear vision of the essential and ideological objective of a university: the comprehensive formation of the human person, viewed in his constitutive and original dignity and in his true end: Society asks the university not only for specialists who are well prepared in their specific fields of knowledge, culture, science and technology, but most of all, for builders of humanity, servants of the community of their brothers and sisters, promoters of justice because they are oriented towards the truth. To put it briefly, today, as always, we need people of culture and science who are able to place the values of conscience above all else, and cultivate the supremacy of being over the apparent. The man of science will truly help humanity if he preserves "the sense of the transcendence of the person over the world and of God over the person" (Discourse to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, 1979, November 10, n. 4).

In this substantial mission the duties of the Athenaeum meet those of the Church. For this reason, the promotion of culture, not disconnected from life, has always been an important element in the Church's activity. Throughout the centuries she has founded schools of all types and levels; besides sending out her missionaries she has also founded prestigious universities, yours among them.

Not strangers but allies

The Church and the university, therefore, must not be strangers to each other, but close and allied. Both of them are dedicated, each according to its own manner and method, to the search for truth, to the progress of the spirit, to universal values, to the integral development of the human person.

An increased, mutual understanding between them cannot but lead to the achievement of these noble goals which unite them. This necessary working together of university and Church finds its expression, both ancient and modern, here in Turin as well. I have been informed, in fact, that the diocesan ecclesial community is directly involved in these problems, especially since seventy-two per cent of those enrolled in the university and the Polytechnic arc from Turin. Furthermore, the various diocesan components play an active role in solidarity, pastoral initiatives and technical assistance in the manifold needs of the students; the teachers have the serious task of animating, with their effective conviction, their intellectual and didactic work and of bearing witness to the possibility of a fruitful synthesis of faith and culture beyond all attempts at ideological instrumentalization. In your university you can count on illustrious and shining examples. I would like to mention expressly Venerable Francesco Faà di Bruno, Professor of Higher Analysis and Astronomy and apostle to the young; the student of the Polytechnic, Pier Giorgio Frassati; nor can I forget the late Cardinal Michele Pellegrino who, before being appointed Archbishop of Turin, was the Ordinary Professor of Ancient Christian Literature in this university. I express my wish that this local Church may continue to offer its sincere collaboration for human advancement and the common good.

My presence in Turin is linked, on this occasion, to the celebrations of the centenary of the death of St John Bosco, as the Rector Magnificus so kindly told you. It is true that this saint, of whom your city is justifiably proud, did not have any particular connection with this university. Nonetheless, despite his incredibly vast activity, he was able to cultivate in himself a solid cultural preparation, joined to his felicitous gifts of literary expression which enabled him to carry out a noteworthy apostolate, He strongly felt the urge to elaborate a culture which was not the privilege of a few, or something removed from the evolving social reality. Therefore he was the promoter of a solid popular culture, which forms the civil and professional consciences of citizens involved in society. However, most of all, the figure of Don Bosco can also be viewed with sympathy and confidence by the university world, because his life and activity were entirely dedicated to the education of youth. The saint, in fact, summed up his educational programme in the famous three-part formula: "Reason, religion, loving kindness”.

As is written in the letter Iuvenum Patris, "the term, 'reason' emphasizes, in line with the authentic view of Christian humanism, the value of the individual, of conscience, of human nature, of culture, of the world of work, of social living, or in other words of that vast set of values which may be considered the necessary equipment of man in his family, civil and political life... 'Reason' invites the young to an attitude of sharing in values they have understood and accepted. He called it also 'reasonableness' because of its necessary accompaniment by the understanding, dialogue and unfailing patience through which the far from easy practice of reasoning finds expression. "It is true that all this takes for granted at the present day an updated and integral anthropology, free from ideological oversimplification. The modern educator must be able to read closely the signs of the times to glean from them the emerging values which are attractive to youth: peace, freedom, justice, communion and sharing, the advancement of woman, solidarity, development, and urgent ecological demands" (n. 10).

Don Bosco further showed an extraordinary interest in the world of work. He had the far-sighted concern to give the young generations a professional competence and an adequate technical training, especially in a city like Turin and a legion like Piedmont which, through advanced centers of industrial production, have spread the scientific creations and discoveries of the Italian genius on a global scale. Notable also was his concern to promote an ever more discerning education to social responsibility, on the basis of an increased personal dignity to which the Christian faith not only gives legitimacy, but also gives energy with incalculable implications (cf. ibidem, n. 18). In this sphere the university, in that it is a centre for the unification of knowledge, an institutional place for the elaboration of humanistic and scientific learning through the constant exercise of reason, has a primary and inalienable task. If development has a necessary economic dimension, nonetheless it must not be limited to that dimension so as not to be turned against those very people whose advancement is desired. The characteristics of a full development, a "more human” one, which - without denying economic demands - is able to remain at the level of the authentic vocation of man and woman, have been set out in the recent encyclical Soilicitudo Rei Socialis, (nn. 28-30).

This presupposes respect for the deepest human values. A development which is not solely economic, is measured and oriented according to this reality and vocation of the person, seen in its globality, that is, according to its interior parameter. People certainly have need of created goods and industrial products, continually enriched by scientific and technological progress.

However, in order to achieve true development it is necessary not to lose sight of this parameter, which is in the specific nature of the person, created by God in his own image and likeness (cf. Soilicitudo Rei Socialis, n. 29).

The educational genius of St John Bosco was manifested in the highest degree in his love for youth. In order to educate, one must love. The third point of his threefold formula speaks, in fact, of "loving kindness". luvenum Patris once again reminds us that "here we are speaking of a daily attitude which is neither simple human love nor supernatural charity alone. It is really the expression of a complex reality and implies availability, sound criteria and an appropriate style of conduct. "Loving kindness is expressed in practice in the commitment of the educator as a person entirely dedicated to the good of his pupils, present in their midst, ready to accept sacrifices and hard work in the fulfillment of his mission. All this calls for a real availability to the young, a deep empathy and the ability to dialogue with them... The true educator therefore shares the life of the young, is interested in their problems, tries to become aware of how they see things,... is ready to intervene to solve problems, to indicate criteria, to correct with prudent and loving firmness blameworthy judgments and behavior. In this atmosphere of 'pedagogical presence' the educator is not looked upon as a 'superior’, but as a “father, brother and friend" (n. 12).

All of this, although considering the specificity of the various areas and goals, is important also in university education; if the university wants to instruct and educate, the energy of love must work in it, as it did in the life, mission and methods of Don Bosco. I therefore wish, with all my heart, that this illustrious Athenaeum, as well as the other specialized advanced schools in Turin, may always be communities attentive to these supreme values, open to these horizons. Certainly, for the intellect to be fully utilized and the heart to be moved by charity, the help of the Logos is necessary, because, as St Augustine says, he is the light: ipse (Filius) est menti nostras lumen (Quaestio Evangelii I, 1; PL 35, 1323); he is love: "amavit nos, ut redamaremus eum” (Enarr. in Ps. 127, 8; CCL, 40, 1872). For those who have accepted this light and love, the work of study, teaching and formation is certainly sustained by this truth; however, I think that all, to whatever ideological group they may belong, will find themselves once again united and agreed on this common platform of intelligent and generous service to the people of tomorrow. For that end, with feelings of the greatest esteem, I invoke the continual assistance of the Word of God for all of you, and as a pledge of this I impart my special blessing.

Source of the English text: L' Osservatore Romano, Weekly Edition, 1988, October 10, pp. 3-4.