On Sunday, 18 April 1982, the Pope John Paul II met with the teaching staffs from the universities in Emilia-Romagna. His Holiness begins by greeting and thanking the rector of the University of Bologna, as well as the other members of his audience. He reminds them of the glorious heritage of the university in Bologna. Next, the Pope explains his reasons for making the address. Historically, the Church has always been involved in the university. Personally, he has committed much of his life to academics. More universally, the Church has a great interest in man and his pursuit of truth. Continuing, the Pope develops the relationship between the Church and the university. Both institutions seek to help man, to cultivate universal knowledge and to develop an authentic vision of truth.

On Sunday, 18 April 1982, the Pope John Paul II met with the teaching staffs from the universities in Emilia-Romagna. His Holiness begins by greeting and thanking the rector of the University of Bologna, as well as the other members of his audience. He reminds them of the glorious heritage of the university in Bologna. Next, the Pope explains his reasons for making the address. Historically, the Church has always been involved in the university. Personally, he has committed much of his life to academics. More universally, the Church has a great interest in man and his pursuit of truth. Continuing, the Pope develops the relationship between the Church and the university. Both institutions seek to help man, to cultivate universal knowledge and to develop an authentic vision of truth.

Church united with university in search for full truth about man

Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen!

It is with deep joy that I meet with you today, members of the teaching staff of the University of Bologna, in whom I recognize and honour the heirs of the oldest university tradition in the world. My joy is increased by the presence of the rectors and professors of the other university seats in the region; that is, the universities of Ferrara, Modena, Parma and the faculty of agriculture of Piacenza.

I cordially greet the Rector Magnificus of the University of Bologna, Prof. Carlo Rizzoli, in whose noble address I discerned not only the expression of the general feelings of cordial deference towards my person, but also the witness of the profound sense of responsibility which animates the academic authorities and the teaching staff as they carry out the daily educative task entrusted to them. In thanking you, Mr. Rector, for your noble words, I also wish to express my gratitude for your kind invitation to visit the present seat of the university. Even if various circumstances did not permit it to occur, I was very pleased to receive the invitation, since it awakened in my mind the memory of the visit which I had the opportunity to make in long-ago 1964 to that distinguished centre of studies when I held the position of Grand Chancellor of the University of Krakow, which celebrated that year the six-hundredth anniversary of its founding

I also thank the On. Tesini, Minister for Scientific Research, who, greeting me in the name of the entire Italian scientific community, opportunely underscored the extraordinary possibilities and fearful risks which accompany scientific progress, as, for example, the events of this century have made clear.

Finally, I wish to address a special word of greeting to the academic authorities and professors of the other university seats in the region. Their presence is eloquent proof of the bond of ideals linking those centres with the Bolognese “alma mater” and with the original university experience, which developed at the beginning of the millennium in this city. It is precisely to render homage to those glorious beginnings that I intend to go soon to the seat of the ancient “Arciginnasio” which was the cradle of the institution of the university according to the model which successively spread throughout Europe and the world.

It is not possible to think of Bologna without its evoking the formative role played by the “alma mater” during the arc of nine centuries. Its value as a centre of studies has caused its fame to spread so far beyond the city walls that it has attracted numerous and worthy students and teachers from every nation, demonstrating the perennial universal dimension of every genuine search for truth. Later on, many other universities were inspired by the model of this singular Universitas, community of teachers and students joined together in the art of teaching and learning, confirming the validity of the cultural choice made nine centuries ago at Bologna.

What a glorious past, therefore, it is to which the university life in this city is heir! But this heritage means responsibility for the future, and you who find yourselves, today, directly confronted with the great problems of the modern university must appeal to the lofty values of your tradition in order to actualize them in a modified situation with renewed creativity.

Historical and personal reasons

Perhaps you will ask me by what authority I, as the representative of the Church, turn to you today with such intense feeling regarding what are your specific duties. You may ask me if I have the right, so to speak, to intrude into the area of your responsibilities. There are various reasons which press me to do so.

There is above all an historical motive: the Church can affirm that it has often been at the origins of the university institution, with its schools of theology and canon law.

There is also, perhaps, if you will permit me, a personal reason, since as you know I dedicated not a small part of my past endeavours to teaching at the university level, so that I feel truly honoured to be your colleague.

But there is a deeper and more universal reason, and it is the mutual passion, yours and the Church’s, for the truth and for man; or rather, for the truth of man. As I have already had occasion to say while addressing the General Conference of UNESCO, the university is one, perhaps the principal one, of those “work benches at which man’s vocation to knowledge, as well as the constitutive link of humanity with truth as the aim of knowledge, become a daily reality, become, in a sense, the daily bread of so many teachers, venerated leaders of science, and around them, of young researchers dedicated to science and its applications, as also of the multitude of students who frequent these centres of science and knowledge.

We find ourselves here, as it were, at the highest rungs of the ladder which man has been climbing, since the beginning, towards knowledge of the reality of the world around him, and towards knowledge of the mysteries of humanity.” (Discourse to UNESCO, no. 19).

Now, if this man, in the full truth of his personal being together with his community and social being, is the first and fundamental path which the Church must travel to fulfil the mission entrusted to it by Christ (cf. Redemptor Hominis, no. 14), you understand why your daily adventure on the roads of learning cannot be indifferent to her.

In fact, if we await from Christ, the new Man, crucified and risen, the final answer to our perennial question “Who is man?”, we address this same question also to you, since that which you are accomplishing with great difficulty is of interest to us. Ours, in fact, is a fides quaerens intellectum, a faith which demands to be reflected upon and, as it were, wedded to the intelligence of man, of this historical concrete man. We would therefore be unfaithful to our own mission if we thought we could avoid the confrontation which is your daily task. As we have been taught by the painful historical experiences of the lack of dialogue between faith and science, the damage would be too great if the Church were to furnish answers which no longer meet the questions man poses today in his conscious climb up the ladder of truth.

The Church is, therefore, united with the university and with its problems, since it knows that it needs the university itself so that its faith may be embodied and become culture; and since the Church affirms that the search for truth is part of man’s very vocation; man, created by God in his image (cf. Discourse to parish priests of Rome on the university apostolate, 8 March 1982).

Relationship between Church and university

But if that which I have said is more generally relevant to the relationship between faith and science, faith and culture, I now wish to relate it more specifically to the relationship between the Church and the university. In fact, the university today, in Italy and in many other countries in the world, finds itself at the centre of some tensions which challenge its deepest reasons for existence and send it in search of its identity, nine hundred years after its birth.

The first of these tensions is that between the specialization of the various disciplines and the idea of the universality of knowledge. The Second Vatican Council observed: “Today it is more difficult than it once was to synthesize the various disciplines of knowledge and the arts. While, indeed, the volume and the diversity of the elements which make up culture increase, at the same time the capacity of individual men to perceive them and to blend them organically decreases, so that the image of universal man becomes even more faint” (Gaudium et Spes, 61). Now it is precisely characteristic of the university, unlike other centres for study and research, to cultivate universal knowledge, not in the sense that it must accommodate the complete range of disciplines, but in the sense that in it every branch of knowledge must be cultivated in the spirit of universality, that is, with the awareness that each one, even though different, is so bound to the others that it is not possible to teach it outside the context, at least in intention, of all others. To close oneself is to condemn oneself, sooner or later, to sterility, it is to risk mistaking as norm of total truth a refined method for analysing and understanding a particular section of reality.

Therefore, the vision of the truth that modern man attains through the venturesome effort of reason cannot but be dynamic and dialogical. Since reason can grasp the unity which binds the world and truth to their origin only within partial modes of knowledge, each single science – including philosophy and theology – is a limited attempt which can grasp the complex unity of truth only in diversity, that is, within a system of open and complementary areas of knowledge (cf. Discourse to men of science in Cologne cathedral, no. 2).

But a method so vital and perennially careful to embody the ideal of the universality of knowledge can only be achieved in a university that is truly a community for research, a meeting place and a place for spiritual encounter in humility and courage, where men who love knowledge learn to respect each other, to consult each other, creating a cultural and humane climate which is as far removed from closed and exaggerated specialization as from lack of precision and relativism. Incomplete points of view will be able to merge, not because forced to do so according to a predetermined plan, but because reciprocal listening and constant contact will allow their complementary nature to be perceived.

Freedom of research

A second tension derives from the ever more decisive role assumed by scientific research in today’s world, so that it is the subject of particular interest on the part of those who hold political and economic power. Therefore the question arises, this, too, fundamental for the university, as to the relationship between the public power and its culture policy, or other powers present in society, and the autonomous initiatives of the university institutions.

Now, the university community will surely have to take responsibly into consideration the expectations of the civil society which surrounds it indeed, the time has passed when the university could think of itself almost as a society closed in itself. These expectations concern both the objectives of the research undertaken, as well as the preparation of the students so that they may adequately practise a profession in society. And in any case it seems to me my duty to affirm once more the principle of relative autonomy of the university institution as a guarantee of the freedom of research. Freedom, in fact has always been an essential condition for the development of a science which preserves its innermost dignity of the search for truth and is not reduced to pure function, used as an instrument of an ideology for the exclusive satisfaction of immediate ends, of material social needs or economic interests, of a view of human knowledge uniquely inspired by unilateral or partial criteria typical of biased, and for that very reason incomplete, interpretations of reality.

Learning can more effectively influence practice according to how truly free it is! Knowledge is, in fact, a total vision of man and his history; it is the harmony of unitary synthesis between contingent realities and eternal Truth. As the Second Vatican Council stated, “culture must be subordinated to the integral development of the human person, to the good of the community and of the whole of mankind. Therefore one must aim at encouraging the human spirit to develop its faculties of wonder, of understanding, of contemplation, of forming personal judgments and cultivating a religious, moral and social sense. Culture, since it flows from man’s rational and social nature, has continual need of rightful freedom of development and a legitimate possibility of autonomy according to its own principles,” (Gaudium et Spes, 59).

Consequently, an interpretation of knowledge and culture which willfully ignores or even belittles the spiritual essence of man, his aspirations to the fullness of being, his thirst for truth and the absolute, the questions that he asks himself before the enigmas of sorrow and death, cannot satisfy the deepest and most authentic needs of man. Such an interpretation is, by itself, excluded from the realm of knowledge, that is, from “wisdom” which is the pleasure of knowing, maturity of spirit, yearning for true freedom, the exercise of judgment and discretion.

Even in its necessary specializations, the university can consequently carry out its essential role in society only if it succeeds in harmonizing that role with regard to the system of relations with transitory, even though all-embracing, ideologies. The defence of culture’s free space is one of the clearest signs of the maturity of a civilized society, but it is also up to the university community itself to demonstrate in a convincing manner the need for it by presenting the fascination of that complete humanism which has always inspired its ideals, and which surely corresponds even now to many secret expectations of our contemporaries.

Community dimension

Finally, I must dwell again on a third and perhaps even more obvious aspect of university problems. The broadened access to a higher culture, undoubtedly a positive phenomenon also in Italian society, has attacked the structures of your institutions, putting them to a hard test and posing problems which regard not only the organization, but also the level and very nature of university teaching and its relationship with scientific research.

Consequently, I believe it is necessary to reaffirm with vehemence the community dimension of the university, also with regard to the relationship between the teaching staff and students. Although this has been made difficult by the increased number of students and the scarce attendance at lectures in the various faculties, human contact is indispensable to the formation of the personality, and therefore essential so that the university may continue to be able to carry out its educative mission. Experience teaches how the personalities of true teachers are important in order to communicate not only the content of knowledge and study methods, but also the personal passion for the truth, the moral commitment which animates research.

That end requires that the teaching staff themselves be constantly engaged in research. One who teaches young people and is no longer capable of carrying on the search, is like someone who wants to quench his thirst by drinking water out of a swamp instead of drinking from a spring. And at the same time it requires that the teaching staff always maintain an attitude of willing service. Knowledge has not been given to them to be kept as an exclusive possession or as a means for gaining personal prestige, but to be divided and shared. It is an experience of deep joy for the person who, by communicating a spiritual good such as wisdom, sees that it does not diminish, nor become exhausted, but multiply, and gain even more that simplicity and clarity which is the mark of truth.

Difficult tasks

Certainly I have had to limit myself to touching upon some fundamental problems which are part of your daily preoccupations and which are extremely complex. But the tradition and ideal to which you are heir are too great, and too great is the prize at stake for the university and the society in which it lives for you to stop in the face of difficulties. You, today, just as the builders of the ancient universities, with imagination and courage cannot refuse the task of dynamically bringing together once more, in a new way suited to modern times, the deepening of the various disciplines and the tendency towards universality of knowledge, the autonomy necessary to free research and the service of society, individual and group research and the teaching of the younger generation.

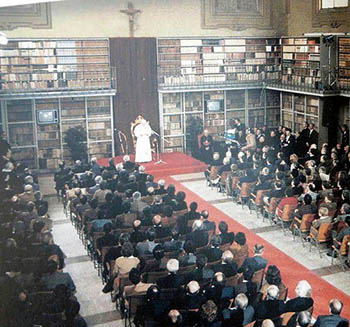

The Church intends to be present in this difficult task, and to collaborate sincerely, in the sole interest of man. In the past, Roman pontiffs and other eminent ecclesiastics have distinguished themselves for their good services to the Bolognese university. It is enough to recall the name of the great Pope Lambertini and the support given by him to the renewal of higher education in this city in the eighteenth century. Today it is the ecclesiastical community as a whole which, in the spirit of the Second Vatican Council, feels itself co-responsible for the encouragement of human and evangelical values in the life of your university. From the concrete commitment to welcoming students coming from outside the city, to the animation of centres and meeting places for cultural dialogue – such as that in which we find ourselves at this moment, in the ancient Dominican convent – there is a whole range of initiatives already existent and possible with which the Christian community can contribute to the facing of the university’s problems. There is above all the active presence in an attitude of research, of dialogue and witness, of Christians, teachers and students alike, who work within the university itself. May their contribution enrich the research community that you constitute so that every receptive mind will recognize that it is not in the true interests of anyone that the contribution of that Catholic tradition, which has had and continues to have such a great part in the history of this country, be lacking in the sources of culture.

The word of truth

All things considered, at the very heart of that vitality which aims for universal knowledge and which inspires your work, do not questions about the final meaning of life and human endeavour arise precisely today with ever greater frequency? Is it not the better young people who come to you thirsting to know, to question you about the legitimacy and finality of science, about moral and spiritual values which will allow them to believe once again in knowledge, in reason and its good use?

If the Christian faith is a fides quaerens intellectum, then the human intellect is an intellectus quaerens fidem an intellect that, in order to rediscover the right faith in itself must open itself trusting to a truth greater than itself. This truth made human and consequently no longer extraneous to every true humanism, is Jesus, the Christ, the word of eternal truth, which the Church heralds as her ultimate contribution for the achievement of your ideal: the knowledge of truth in its full measure.

Source of the English text: L' Osservatore Romano, Weekly Edition, 1982, May 10, pp. 9, 12.