1. Prof. Pinsent, you live and teach in the same town where John Henry Newman worked and preached for most of his life. How is Newman’s memory still present, today, in Oxford?

Newman’s memory is very much present in Oxford today, in part because of the university’s Catholic heritage and the many Catholic institutions in the city. For example, the buildings of the university chaplaincy are called “The Newman Rooms,” and the Oxford Oratory of St Philip Neri, established in 1993, builds on the work of the first English oratory established by Newman in Birmingham in 1848. Newman’s life and works are frequent topics of public talks and academic events.

Oxford in general and Anglicans in particular have other good reasons for remembering Newman. During his lifetime he was a prominent member of the university, being a fellow of Oriel College from 1822 to 1846, the Anglican Vicar of the University Church from 1828 to 1843, and one of the founders of what became known as the “Oxford Movement,” which emphasised the Catholic heritage of Anglicanism. The Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, established by Pope Benedict XVI in 2011, is a fruit of this movement. Many of Newman’s works, such the Grammar of Assent and the Idea of a University continue to attract academic attention at the university even by those who do not share Newman’s faith.

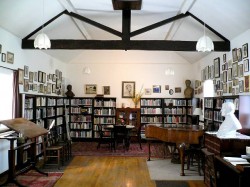

For these reasons and others, there will be many events in the city during this year of Newman’s canonisation. For example, the Oxford Oratory is organising a lecture by Bishop Robert Barron at the University Church on 16 October with the title, “Newman and the New Evangelisation.” Oriel College maintains Newman’s personal oratory and is also marking his canonisation in various ways, including hosting a recent visit from HE Cardinal Gerhard Müller as well as events in Rome on 12 and 13 October.

2. You are research director of the Ian Ramsey Centre for Science and Religion. Which aspects of Newman’s thought you think valuable and illuminating for today’s dialogue between theology and science?

The aspect of Newman’s thought which I consider to be most important today is not about theology and science directly but rather his uncompromising focus on the salvation of our souls, and his constant effort to distinguish merely natural goals from the goods of the supernatural life of grace. Frequently in his sermons, for example, he will highlight someone who appears to be an exemplar of civic virtue but who still lacks the life of grace, which is what one needs to become a saint. I take great encouragement from this focus on salvation and the distinction of nature and grace.

Given especially that these topics are scandalously neglected in the contemporary Church, I try to copy Newman’s example in my life, research, and preaching. For example, much of my research focuses on the distinction of the virtues of the life of grace, described by St Thomas Aquinas in his Summa theologiae II-II.1-170, and the virtues of nature alone, described by Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Contemporary science also offers important new metaphors for grace, metaphors that are echoed in Newman’s motto, “Heart speaks unto heart.” I address this topic in my book, The Second-Person Perspective in Aquinas’s Ethics: Virtues and Gifts (Routledge, 2012).

As regards theology and science more generally, the clear sense of Newman’s work is that once one has made the correct distinctions, as he does, then there is certainly no question of a conflict of theology and science. For the most part, these worlds of discussion and research are distinct in both subject and method.

3. John Henry Newman lived in the same century as Charles R. Darwin. In letters addressed to his friends, Newman commented on the findings of the English biologist. Could you, please, shortly resume Newman’s thought on the evolution of the human being?

John Henry Newman not only shared the same century as Charles R. Darwin but a similar attitude to the natural theology of the early nineteenth century, as exemplified in William Paley’s influential book of that name. Newman was deeply suspicious of the purported cognitive or moral benefits of natural theology, as can be seen, for example, by his comments on this topic in his sermon, “The Religion of the Day”. For Newman, this suspicion is rooted in an Augustinian sense of the utter inadequacy of human nature to know and love God without divine grace.

As regards Newman’s thoughts regarding evolution, I note that inters.org has already published a letter of John Henry Newman to J. Walker of Scarborough, a letter that I recommend to readers. What is striking is that Newman describes himself in this letter as less critical of Darwin than a contemporary critic. He goes on to write, “It does not seem to me to follow that creation is denied because the Creator, millions of years ago, gave laws to matter. He first created matter and then he created laws for it — laws which should construct it into its present wonderful beauty, and accurate adjustment and harmony of parts gradually.” Readers should note that Newman’s sentences here echo Darwin’s comment in the conclusion of the Origin of Species, “To my mind it accords better [i.e. than the independent creation of each species] with what we know of the laws impressed on matter by the Creator, that the production and extinction of the past and present inhabitants of the world should have been due to secondary causes, like those determining the birth and death of the individual.” Newman certainly defends the uniqueness of human beings, but his comments in this letter underline that evolution in general does not need to be considered as atheistical or anti-Christian.

4. Among the themes that Newman placed at the centre of his reflection there is the love of truth. He sought truth with passion, accepting all the consequences of his choices. Was his vision of truth too ideal, compared to the contemporary tendency to avoid strong theses and firm tones?

In the first lecture of his series, Certain Difficulties Felt by Anglicans in Catholic Teaching, Newman states that “there is but one thing that forces me to speak,—and it is my intimate sense that the Catholic Church is the one ark of salvation, and my love for your souls;…” In other words, the vision of truth is presented in these lectures solely out of love and a concern for the salvation of his listeners or readers.

This point is underlined in lecture 8, section 4, of the same work, “The Catholic Church holds it better for the sun and moon to drop from heaven, for the earth to fail, and for all the many millions on it to die of starvation in extremest agony, as far as temporal affliction goes, than that one soul, I will not say, should be lost, but should commit one single venial sin, should tell one wilful untruth, or should steal one poor farthing without excuse.” With these words, Newman is not claiming that care for the environment, or feeding the earth’s population, are unimportant. But he wants to put these goals into the correct supernatural perspective, namely that the integrity of our relationship to God, damaged by a single venial sin, ultimately outweighs the preservation of life, health, and earthly happiness of millions, as goals considered solely in themselves. Whether we end up in God’s presence, or in hell, we shall presumably make the same judgment, but Newman’s gift is to warn us clearly while we still have time to receive grace. Such clarity is infinitely preferable, in my view, to the ambiguous and often anti-supernatural styles of preaching and writing that are common today.

5. If you wished to approach young scholars to the thought of the Oxford philosopher, which book among Newman’s works you suggest start with?

Given that scholars have a wide range of interests and priorities, any general recommendations I make will have limited value, especially as Newman wrote an extraordinary amount on so many topics. Besides the many published editions of his works, we all owe an enormous debt of gratitude to those who have painstakingly made so much of this material freely available online (e.g. www.newmanreader.org). A good first step can be to use these tools to browse beyond the more famous works, such as the Apologia Pro Vita Sua. A further advantage of browsing Newman’s works directly is that one can also circumvent those commentators who love to misrepresent Newman, or to soften his focus on salvation and grace as the most important priorities of our lives.

Among the less fashionable or well-known works, I recommend the lecture series noted previously, Certain Difficulties Felt by Anglicans in Catholic Teaching. I consider this work to be the final word on the limitations of Anglicanism or, more broadly, a life of merely civil virtue, and the need to live a life of grace in full communion with the Catholic Church. I also strongly recommend his Parochial and Plain Sermons, which have become my main spiritual reading for the last two years.