John Kepler (1571-1630) is one of the most interesting figures in the history of modern thought. The German astronomer managed to combine the demands of the new science of nature with his religious faith, in an effective synthesis that characterized all his research and, more generally, the entire course of the Scientific Revolution. This year (2018) marks the 400th anniversary of one of his fundamental discoveries, the third law of planetary motion. Kepler’s third law states the proportion between the square of planets’ revolution time and the cube of their average distance from the Sun (T2 = K R3). In May 1618, Kepler had already fine-tuned all the details of his theory, although the printing of the Harmonices Mundi, the work containing the third law, was completed in Linz only during the summer of the following year. The publication of his book happened during a particularly troubled period in Kepler's life, a period marked by several negative vicissitudes, such as his mother's witchcraft trial and various family losses. The attention he devoted to the elaboration of this theory and the achievement of such a relevant result helped him in that difficult phase of his existence. In the months preceding the discovery of the third law, he managed to forget about the negative events and focused on his work. The dedication to such an important project, and the considerable results already achieved in the past, were the right incentives to continue his investigations.

John Kepler (1571-1630) is one of the most interesting figures in the history of modern thought. The German astronomer managed to combine the demands of the new science of nature with his religious faith, in an effective synthesis that characterized all his research and, more generally, the entire course of the Scientific Revolution. This year (2018) marks the 400th anniversary of one of his fundamental discoveries, the third law of planetary motion. Kepler’s third law states the proportion between the square of planets’ revolution time and the cube of their average distance from the Sun (T2 = K R3). In May 1618, Kepler had already fine-tuned all the details of his theory, although the printing of the Harmonices Mundi, the work containing the third law, was completed in Linz only during the summer of the following year. The publication of his book happened during a particularly troubled period in Kepler's life, a period marked by several negative vicissitudes, such as his mother's witchcraft trial and various family losses. The attention he devoted to the elaboration of this theory and the achievement of such a relevant result helped him in that difficult phase of his existence. In the months preceding the discovery of the third law, he managed to forget about the negative events and focused on his work. The dedication to such an important project, and the considerable results already achieved in the past, were the right incentives to continue his investigations.

The Keplerian idea of a mathematical-musical harmony of the heavens can be found in the works of other modern authors. Kepler, however, was also inspired by the harmonic structure of the planetary movements acquired by reading ancient works. Among these, besides the Platonic dialogues and texts of the Pythagorean philosophers, we point out the importance of Claudius Ptolemy’s Harmonics (ca. 100 A.D. – ca. 175 A.D.), whose manuscript was provided to him by his friend and correspondent Herwart von Hohenburg and whose contents were particularly appreciated by Kepler. Another author who had a significant influence was the neo-platonic Proclus (412-485) who, in the commentary to the first book of Euclid's Elements, spoke of geometric figures as the foundation of the matter’s real structure. In the autumn of 1617, a few months before the discovery of the third law, Kepler also read the Dialogo della Musica Antica e Moderna by Vincenzo Galilei (1520-1591), musical theorist and father of the most famous Galileo, who studied the concepts of consonance and dissonance. However, the Keplerian scientific project brings together other essential elements, such as the crisis of the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic cosmological model and the advent of modern mathematical realism. According to Kepler, in our soul there are the mathematical paradigms that enable us to grasp through the senses the proportions evident in the world around us. The soul essentially is harmony, and there are three disciplines based on harmony itself: geometry, music and astronomy. The human mind, made in the image of the divine mind, has within itself the forms and laws of geometry which, in turn, are based on the same numerical relationships that determine the other two disciplines. Therefore, there is a direct correspondence between the numerical ratios of musical harmonies and those of geometric laws. This is the reason why the movements of the planets, structured by the supreme intelligence of God, must be interpreted in the light of the harmonic beauty at the base of creation and given by God to the human being. The book of nature, part of the Revelation, manifests itself to humanity in all its extraordinary precision, as the study of astronomy unveils. The search for mathematical elegance in planetary trajectories characterizes the activity of the astronomer – which Kepler defines as the “priest of nature” – since he studies the regularity wanted by God himself. Performing astronomical calculations, therefore, means interpreting the Creator's own thoughts, and explaining the celestial harmonies of the planets means expressing gratitude to the Author of natural harmony. One can see, in all of this, the influence of the principle of analogy which has been decisive for the achievement of modern scientific thought. Kepler’s Christian faith cannot be seen as a simple psychological element; it constitutes a spiritual dimension that indicates the only viable way for science, as it at the same time advances problems and indicates their solutions. The method adopted by Kepler is mainly deductive, as he starts from the conviction about the geometric structure of the universe to interpret the data of astronomical observation. This is how our scientist has managed to interpret the large amount of data collected by Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) and his school, and to formulate his three laws. The principle of universal harmony leads him to reject the idea of the infinite dimensions of the universe (even though in Kepler’s theory, the dimensions of the world are larger than in Copernicus’ theory). Infinity is not measurable and actual infinity would be in contradiction with the creation of cosmic harmony as an essential factor of revelation.

Kepler's theory about the relationship between science and biblical exegesis also as a place in this cosmological-theological view. The Bible is not a scientific book and in its verses there are no references to the physical structure of the universe. The introductory words of Astronomia Nova (1609) leave no doubt about this:

"There are, however, many more people who are moved by piety to withhold assent from Copernicus, fearing that falsehood might be charged against the Holy Spirit speaking in the scriptures if we say that the earth is moved and the sun stands still. […]Thus, many times each day we speak in accordance with the sense of sight, although we are quite certain that the truth of the matter is otherwise. […] Thus Christ said to Peter, "Lead forth on high," (Lk 5:4) as if the sea were higher than the shores. It does seem so to the eyes, but optics shows the cause of this fallacy. Christ was only making use of the common idiom, which nonetheless arose from this visual deception. Thus, we call the rising and setting of the stars "ascent" and "descent," though at the same time that we say the sun ascends, others say it descends. […] Now the holy scriptures, too, when treating common things (concerning which it is not their purpose to instruct humanity), speak with humans in the human manner, in order to be understood by them. They make use of what is generally acknowledged, in order to weave in other things more lofty and divine. No wonder, then, if scripture also speaks in accordance with human perception when the truth of things is at odds with the senses, whether or not human s are aware of this. […]Now God easily understood from Joshua's words what he meant, and responded by stopping the motion of the earth, so that the sun might appear to him to stop. For the gist of Joshua's petition comes to this, that it might appear so to him, whatever the reality might meanwhile be. Indeed, that this appearance should come about was not vain and purposeless, but quite conjoined with the desired effect. […] A generation passes away says Ecclesiastes (Eccl 1:4), and a generation comes, but the earth stands forever. Does it seem here as if Solomon wanted to argue with the astronomers? No; rather, he wanted to warn men of their own mutability, while the earth, home of the human race, remains always the same, the motion of the sun perpetually returns to the same place, the wind blows in a circle and returns to its starting point, rivers flow from their sources into the sea, and from the sea return to the sources, and finally, as these men perish, others are born. Life's tale is ever the same; there is nothing new under the sun. You do not hear any physical dogma here. The message is a moral one, concerning something self-evident and seen by all eyes but seldom pondered. Solomon therefore urges us to ponder. Who is unaware that the earth is always the same? Who does not see the sun return daily to its place of rising, rivers perennially flowing towards the sea, the winds returning in regular alternation, and men succeeding one another?" [1]

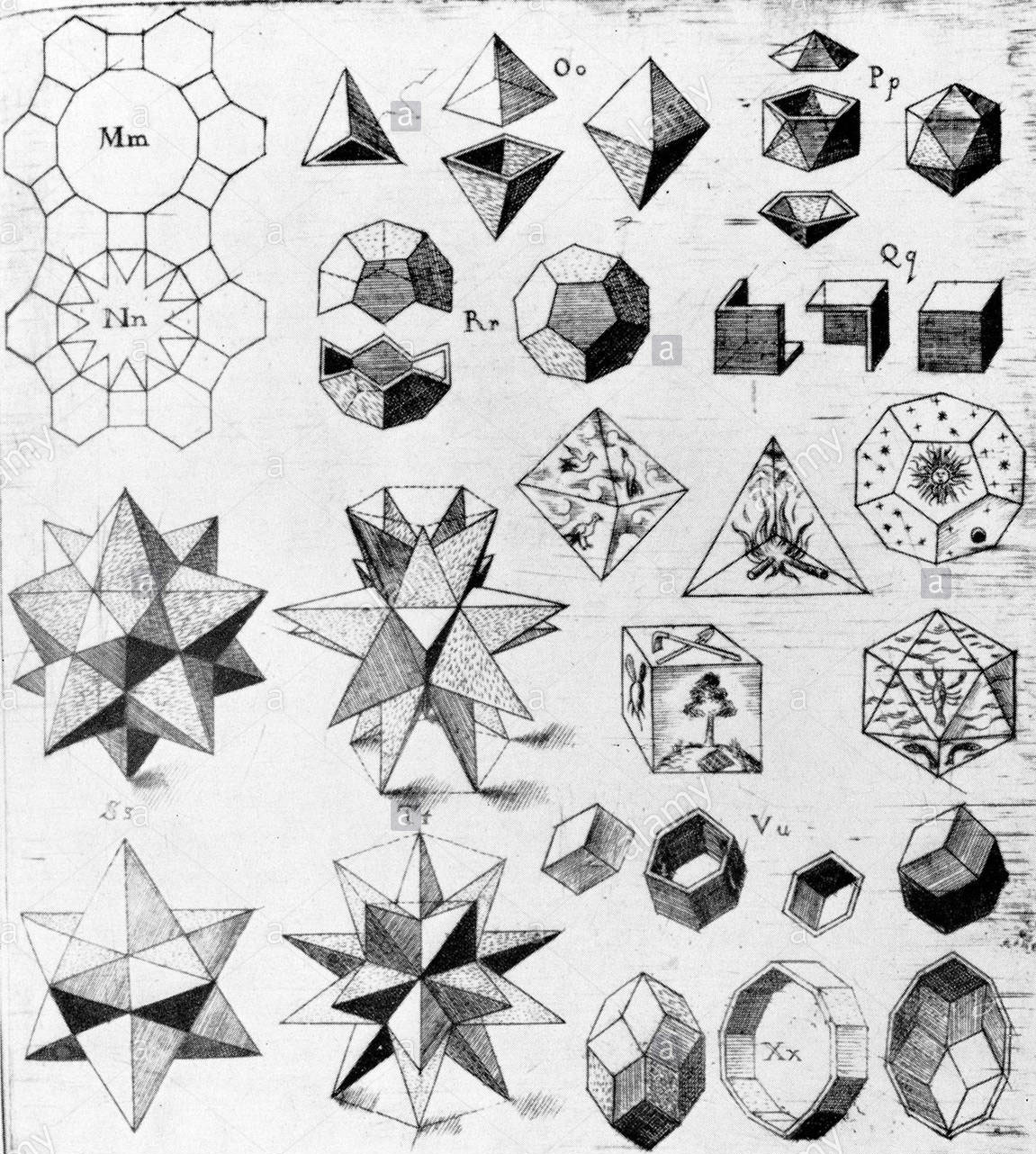

With the publication of the Harmonices Mundi (1619), Kepler completed the research programme he had planned since the Mysterium Cosmographicum, published in 1596. In the early stages of his studies, he was mainly interested in understanding the meaning of the divine design at the time of creation; the initial attempt to insert the five regular solids (cube, tetrahedron, dodecahedron, icosahedron, octahedron) to determine the distances of the planets from the sun, however, did not convince him. In the end, the mathematical relationship between the square of the times of revolution and the cube of the average distance of the planets from the Sun represented the crowning of his enormous intellectual effort. This discovery, moreover, had a decisive influence on the work of Isaac Newton (1642-1727), who started from Kepler's work to find the law of universal gravitation. In the Keplerian vision, in fact, planetary movements are the result of a real energy emanating from the Sun. Moreover, the fact of placing the sun in one of the fires of elliptical trajectories implies the coincidence between mathematical description and physical reality, helps rejecting the idea that astronomical science is only to "save phenomena". Although the explanation of planetary motion in terms of quasi-magnetic forces was later abandoned, this third law has reinforced within the modern astronomer community the idea of planetary motion as the effect of a combination of geometric models and celestial forces.

In this way it is understood in what sense Kepler believed in the existence of a universe according to the original meaning of the term (unum in diversis). In his conception, the planets move in a global cosmic harmony, based on divine mathematical archetypes. In other words, the musical harmony of the heavens is not a trivial metaphor and this structure of the world depends on the fact that it reflects that of the Divine Trinity, with the Sun representing the Father, the Earth symbolizing the Son and space symbolizing the Holy Spirit. It is precisely the similarity between the Divine Persons and the structure of the cosmos that confers to the latter the rational and organismal character, in a final synthesis in which the scientific and theological dimensions are inseparable. The third law, like the first two announced in the Astronomia Nova, is the result of that basic vision that has animated all his research. The universe, according to Kepler, was ordered by God according to precise mathematical relationships that the human being, made in the image and likeness of the Creator, must discover. Human research will never allow man to share the totality of the divine essence, but only the mathematical principles that govern nature. Astral movements, therefore, are not only an effect of the energy emanating from the Sun, but are the result of a designed universal harmony able to balance the same energy and other numerical characteristics of the planets, such as their distances and dimensions.

The reading of some particularly significant passages of this work highlights Kepler's willingness to pursue his scientific goal, i.e. confirming the existence of precise mathematical relationships in the celestial motions. In the Proemio he reiterates that geometric figures constitute the archetypes of the divine mind and, therefore, precede their concretization in creation and their presence in the human mind.

The reading of some particularly significant passages of this work highlights Kepler's willingness to pursue his scientific goal, i.e. confirming the existence of precise mathematical relationships in the celestial motions. In the Proemio he reiterates that geometric figures constitute the archetypes of the divine mind and, therefore, precede their concretization in creation and their presence in the human mind.

At the beginning of Book III, Kepler first lists some mathematical principles necessary to explain the "causes of consonances", then again affirms the divine origin of astronomical science, which also possesses evident affinities with Platonic thought:

"Then contemplation of these axioms, especially of the first five, is lofty, Platonic, and analogous to the Christian faith, looking towards metaphysics and the theory of the soul. For geometry, [...] is coeternal with God, and by shining forth in the divine mind supplied patterns to God, as was said in the preamble to this Book, for the furnishing of the world, so that it should become best and most beautiful and above all most like to the Creator. Indeed all spirits, souls, and minds are images of God the Creator." [2]

Mathematical archetypes allow man to see the beauty of creation and create that numerical harmony thanks to which men orient their daily actions:

"Then since they have embraced a certain pattern of the creation in their functions, they also observe the same laws along with the Creator in their operations, having derived them from geometry. Also they rejoice in the same proportions which God used, wherever they have found them, whether by bare contemplation, whether by the interposition of the senses, in things which are subject to sensation, whether even without reflection by the mind, by an instinct which is concealed and was created with them. [...] So let the third example, and the one which is proper to this Book, be that of the human soul, and indeed also that of animals to a certain extent. For they take joy in the harmonic proportions in musical notes which they perceive, and grieve at those which are not harmonic. From these feelings of the soul the former (the harmonic) are entitled consonances, and the latter (those which are not harmonic) discords. But if we also take into account another harmonic proportion, that of notes and sounds which are long or short, in respect of time, then they move their bodies in dancing, their tongues in speaking, in accordance with the same laws. Workmen adjust the blows of their hammers to it, soldiers their pace. Everything is lively while the harmonies persist, and drowsy when they are disrupted." [3]

In the tenth chapter of book V, the author expresses all his thanks to God who allowed him to complete such an important research and to grasp the mathematical structure of his creative work:

"I thank Thee, Creator Lord, because Thou hast made me delight in Thy handiwork, and I have exulted in the works of Thy hands. Lo, I have now brought to completion the work of my covenant, using all the power of the talents which Thou hast given me. I have made manifest the glory of Thy works to men who will read these demonstrations, as much as the deficiency of my mind has been able to grasp of its infinity." [4]

In the concluding words of this book, the reader is invited to praise God for creation which is a clear demonstration of God's love for man. The mathematical order of the universe, that is, the essence of the sapiential dimension of creation itself, is the reason that must lead men to exalt the Creator. With reference to the well-known biblical passage Col 1:16-17, Kepler emphasizes the inferiority of the human mind over the divine mind, but at the same time reaffirms that celestial mathematical proportions are the privileged way for the contemplation of universal beauty:

"Great is our Lord, and great is His excellence and there is no count of His wisdom. Praise Him heavens; praise Him, Sun, Moon, and Planets, with whatever sense you use to perceive, whatever tongue to speak of your Creator; praise Him, heavenly harmonies, praise him, judges of the harmonies which have been disclosed; and you also, my soul, praise the Lord your Creator as long as I shall live. For from Him and through Him and in Him are all things, “both sensible and intellectual,” both those of which we are entirely ignorant and those which we know, a very small part of them, as there is yet more beyond. To Him be praise, honor, and glory from age to age. Amen." [5]

Ultimately, the Harmonices Mundi is the result of a great cosmic vision in which science, philosophy, art and theology converge. It is a unique conceptual synthesis, realized by a brilliant mind and always aiming at the discovery of natural laws inserted in the plan of creation. Kepler's work must also be considered as yet another demonstration of the fact that exact science was born within the Christian tradition and thanks to authors who saw the universe as a creature structured by God, according to precise numerical relationships. In the past, too hasty historical reconstructions or those influenced by prejudicial conceptions have superficially affirmed the existence of a rational logic of scientific discourse in opposition to the uncertainty of the presuppositions of the faith. Overall, Kepler's work is one of the most significant denials of this position, which is absolutely unjustifiable from a historical point of view.

[1] Johannes Kepler, New Astronomy, engl. tr. William H. Donahue (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 59-64.

[2] J. Kepler, The Harmony of the World, edited and translated by E.J. Aiton, A.M. Duncan, J.V. Field (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1997), p. 146.

[3] Ibid, pp. 146-147.

[4] Ibid, p. 491.

[5] Ibid, p. 498.