525. What relates to the distinction between the mind matter, the manner in which the mind acts on the body, I have already investigated in the First part, from Art. 153 on, after rejecting the pre-established harmony of the followers of Leibniz. Here I will first of all consider more fully this distinction; I will add something with regard to the mind itself, the force of its actions, its nature; these are closely connected with the very themeofthiswork. After that, I will proceed to consider that which always ought tobe the most profitable of all philosophical meditations, namely, the power wisdom of the Author of Nature.

526. Here, in the first place, it is clear how great a distinction there is between the body the mind, between those things that we term corporeal matter those which we feel in our spiritual substance. In Art. 153, we did everything by the sole means of local distances forces that are nothing else but propensities to local motions, or propensities to change, or preserve, local distance in accordance with a certain necessary law; these do not depend on any free determination of the matter itself. But I do not recognize any representative forces in matter itself- I do not know whether those, who use the term, are really sure of what they mean by it - nor do I attribute to it any other type of forse or action besides that one which has to do with local motions mutual approach recession.

527. But in this substance of ours, by which we live, we feel recognize, by an inner sense thought, another two fold class of operations; one of which we call sensation, the other thought or will. Without any doubt, the idea which we have within us, which is altogether the result of experience, of the former, is far different to that which we have of local distance motion. Indeed I am quite of the opinion, as I remarked in the First Part, that there is in our minds a certain force, by means of which we obtain full cognition of our very ideas those non-local, but mental, motions that we observe in our own selves; we can distinguish between like unlike, as we assuredly do, when after the idea of a horse that has been seen there presents itself the idea of a fish, we say that this is not a horse; or when, in elementary principles, we join together affirmatively like ideas, separate unlike ideas with a negation. Indeed, we also see immediately the nature origin of these non-local motions ideas. Hence, it is self-evident to us that some of them arise through a substance external to the mind, altogether different from it, but yet in connection with it, which we call the body; that others take rise from direct encounter with the mind itself, spring from a far different force. We see that to the first class belong sensations direct ideas, to the second all kinds of reflections, decisions, trains of reasoning, the numerous different acts of the will. By this internal evidence, their own consciousness, even those, who would like to doubt the existence of bodies, other objects external to themselves, affect idealism egoism, are forced to refuse, though unwillingly, their in ward assent to such very absurd doubts. As often as directly, or even reflectively seriously, they think, speak, or act, they are forced so to act, speak, or think, that they recognize other entities situated external to themselves, which are like to themselves, both spiritual material. For, they would not write publish books, or try to corroborate their theory with arguments ; unless they were fully persuaded that, external to themselves, there exist those who will read what they have written published in printed form, those who will hear the reasons they have spoken, at length acknowledge themselves convinced.

528. Now, certain local motions in our body are engendered by impulse from external bodies, or even self-produced by the manner in which they come from without, these are carried to the brain. For in the brain, somewhere, it seems that the seat of the mind must be situated; that is why so many nerve-fibres extend to it, so that the impulses can be carried to it, propagated either by a volatile juice or by rigid fibres in all directions, from it control can be exercised over the whole body. From these local motions there arise certain non-local motions in the mind, that are not indeed free motions, such as the ideas of colour, taste, smell, sound, even grief, all of which indeed arise from such local motions. But, on the evidence of our inner consciousness, by means of which we observe their nature origin, they are something far different to these local motions; that is to say, they are vital actions, although not voluntary. Besides these we also perceive in our own selves that other kind of operations, those of thinking willing. This kind some people also attribute to brutes as well; all philosophers, except a few of the Cartesians, already believe that the first kind of operations is common to the brutes ourselves. The followers of Leibniz attribute a mind even to the brutes, although one that does not act directly on the body. But of those who attribute to the brutes the power of thinking willing, all those that have any understanding admit that in the brutes it is far inferior to our own; so dependent on matter, that without it they cannot live or act; while they believe that our minds, even if separated from the body, are capable of exercising the same acts of thought will just as well.

528. Now, certain local motions in our body are engendered by impulse from external bodies, or even self-produced by the manner in which they come from without, these are carried to the brain. For in the brain, somewhere, it seems that the seat of the mind must be situated; that is why so many nerve-fibres extend to it, so that the impulses can be carried to it, propagated either by a volatile juice or by rigid fibres in all directions, from it control can be exercised over the whole body. From these local motions there arise certain non-local motions in the mind, that are not indeed free motions, such as the ideas of colour, taste, smell, sound, even grief, all of which indeed arise from such local motions. But, on the evidence of our inner consciousness, by means of which we observe their nature origin, they are something far different to these local motions; that is to say, they are vital actions, although not voluntary. Besides these we also perceive in our own selves that other kind of operations, those of thinking willing. This kind some people also attribute to brutes as well; all philosophers, except a few of the Cartesians, already believe that the first kind of operations is common to the brutes ourselves. The followers of Leibniz attribute a mind even to the brutes, although one that does not act directly on the body. But of those who attribute to the brutes the power of thinking willing, all those that have any understanding admit that in the brutes it is far inferior to our own; so dependent on matter, that without it they cannot live or act; while they believe that our minds, even if separated from the body, are capable of exercising the same acts of thought will just as well.

529. Again, of those who attribute to brutes the power of thought will, some apply to either class the term "spirit", but distinguish between two differnt kind of spirits; others attribute the name of spiritual sibstance to these only that can think will without any connection with the body, without any organic disposition of matter, the motion that is necessary to the brutes in order that they may live. This may quite easily be reduced to a quarrel over a mere term, the idea that is assigned to the word spirit, or spiritual, of which the Latin is "a tenuous breath." There will not be original signification merely any great difficulty over the use of the terms, so long as matter (which is devoid of all power of feeling, thinking willing) living things possessed of feeling are carefully distinguished from one another; also amongst living things, the immortal mind,on account of it, in addition also every organic body capable of thinking willing, from the far more imperfect brute; either, because they have the power of feeling only, are unable to think or will; or because, if they do think will, they have these powers far more imperfectly, if the connection with the body is destroyed by some corruption of the organic body, they perish altogether.

530. Besides, there is certainly a very great difference between thinness of the plate, which determines one coloured ray of light rethar than another to be reflected, so that it comes to the eyes, in which sense ordinary people craftsmen use the term colour; the disposition of the points forming a particle of light, to which corresponds a definite degree of refrangibility, in certain circumstances a definite interval between the fits of easier reflection easier transmission, whence there arises the fact that it makes a definite impression upon the nerves of the eyes, in which sense the term colour is used by investigators in Optics; the impression itself that is made upon the eyes, propagated to the brain, in which sense anatomists may employ the term; something far different, of a diverse nature to all the foregoing, being not even analogous to them, or only with a kind of analogy, total similitude that is sufficiently close, is the idea itself, which is excited in our minds, which, determined at length by the former local motions, we perceive within ourselves; our inner consciousness, the force of the mind, concerning the existence of which within us there cannot be the slightest doubt, warn us with no uncertain voice about the matter, make us acquainted with it.

531. Now, the intercourse between the mind the body, which we term union, has three kinds of laws different from one another; of these, two are also quite different also from that which obtains between points of matter; while the third in some sort agrees with it, but is so far different from it in very many other ways that it is altogether remotefrom any material mechanism. The two former are especially applicable to local motions, of our organic bodies, or rather of part of them, whether that part consists of a very tenuous fluid, or of solid fibres; to motions that are not local motions, but to mental motions of our minds, such as the excitation of ideas, acts of the will. According to each of these laws, certain acts of the mind are transmitted to certain motions of the body, vice versa; each kind demands, amongst other things, a certain relative situation of parts of the body, a certain situation of the mind with regard to these parts. For, when this mutual situation between the parts is sufficiently disturbed by a sufficiently great lesion of the organic body, observance of these laws ceases; nor indeed does it hold, if the mind is far away from the body situated outside it.

532. Moreover, of such laws there are two kinds; the one kind is that in which the connection is necessary, while in the other the connection is free. For, we have both necessary free motions; it often happens that one who is stricken with apoplexy loses all power of free motions, at least with respect to some of his limbs; while he retains the necessary motions, not only those which relate to nutrition, depend solely upon a mechanism, but also those by which sensations are excited. From which it is also clear that the instruments which we employ to produce the two different kinds of motions must be different. Also, although in the second kind of these laws it may happen that there is, even in it, some sort of necessary connection, yet it is not a mutual connection. Thus, the whole of our power of free action consists of the excitation of acts of the will, by means of these of ideas of the mind also; once these have been excited by a free intrinsic motion of the mind, owing to a law of this second kind there must immediately arise certain local motions in that part of the body which is the prime instrument of free motions; but there may be no motions of any part of the body, no motions of the mind, which determine the mind to this rather than to that free act of the will. It may happen, possibly, that by a certain law there is an inclination to one thing that the motions produce some acts more easily than others; yet, because there always remains in the mind that faculty of it which we call the will a perfectly free power of choosing even that thing against which it is naturally inclined, there will even be a power of bringing it about that, due merely to its own determination, the thing, which independently of this determination would have the less force, will preponderate. However, in this same kind of law, there will be also certain connections of the necessary type between the local motions of the body the ideas of the mind, together with some involuntary affections of the mind; how many of these laws there may be, how different they may be, whether all the several kinds can be reduced to a single law of fair generality, is indeed, at least up till now, quite impossible to determine.

533. The third kind of law agrees with the mutual law of points in the fact that it pertains to local motion of themind itself, to definite position which it haswith regard to the body, to the definite arrangement of the organs. Thus, while the arrangement persist, upon which life depends the mind must of necessity change its position, as the body changes its position, that on account of some connection of the necessary type, not a free connection. For, if the body rushes headlong through its own gravity, or is vigorously impelled by another, or if it is borne on a ship, or if it progresses through the will of the mind itself, in every case the mind also must necessarily move along with the body, keep to its seat with respect to the body, accompany the body every where. But if this connection of the organic instruments is dissolved, straightway it goes off leaves the body which is now useless for its purposes. But this law of forces governing the local motion of the mind differs greatly from the law of forces between points of matter in this, that it does not extend to infinity, but only to a fairly small distance, that it does not contain that great alternation of propensity for approach recession, going with as many limit-points; or at least we have no indication of these things. Perhaps too, even at very small distances from any point of matter, it has no propensity for recession, since it seems rather to have a power of compenetration with matter. For, I do not think that it can with certainty be decided from phenomena, whether there is compenetration with any point of matter or not. Secondly, it has no lasting unvarying forces of this kind; for they are destroyed as soon as the organization of the body is destroyed; nor are there forces with things like itself, that is to say other minds, so there can be no impenetrability existing between them; nor can there be those connections of cohesion from which the sensibility of matter arises. From the number of these differences special characteristics, it is fairly evident how far even this law pertaining to the union of the mind with the body differs from a material mechanism, that it is something of quite a different nature.

534. We are quite unable to ascertain with any certainty from phenomena alone the position of the seat of the mind. That is to say, we cannot ascertain whether it is present in any definite number of points, has such a virtual extension through the whole of the intermediate space, as, in Art. 84, we rejected in the case of the primary elements of matter. It cannot be ascertained whether it has compenetration with some one point of matter,united with this, bears along with itself those necessary free motions, so that either this point acts on certain other points with even other laws, or so that, certain definite motions being produced in this point, others take place on account of the law of forces that is common to the whole of matter. It cannot be ascertained whether it exists in a single point of space, which is unoccupied by any point of matter, on that account has a connection with certain definite points, with respect to which it has all those laws of local mental motions, of which we have spoken. We can never become acquainted with any of these points from the phenomena of Nature alone certainly, indeed, as i think, neither can we by reflection or any consideration whatever, that may be made with regard to these phemomena.

535. For, in order to determinate it from any consideration of phenomena in any way: it would be necessary to know wheter these phenomena coul happen in any of these ways, or rather some particular one them is required, determined as a conjuction, also local, of the mind with a great part of the body,or even with the whole of th ebody. But to know this, it would be necessary to have a clear knowledge of their laws, which conjunction of the mind with the body necessitates , also a knowledge of the entire disposition of all the points constituting the body, the laws for the mutual forces between points of matter. In addition, there would be the necessity for as great geometrical powers, as would be enough to determine all the motions, which might be produced merely on account of the mechanical distribution of these points. All of these would be needed for perceiving whether, from the motions, which the mind could induce, by the power of its own will or the necessity of its nature, on a single point, or on certain given points, by means of the single law of forces common to points of matter, there could follow all the other motions of the spirits nerves, such as take place in our voluntary motions; as well as all those different motions of particles of the body upon which depend secretions, nutrition, respiration, other motions of ours that are not voluntary. But all these are unknown tous; nor may we aspire to such asublime kind of geometry, for as yet we can not altogether determine all the motions of even three little masses, which act upon one another with forces that are known.

536.There have been some who would confine the mind to some very small portion of the body; for instance, Descartes suggested the pineal gland. But, later, it was discovered seat of the mind that it could not be contained in that part alone; for, if that part were removed, life still it cannot be proved went on. It has been already discovered that life endured for some time without the extend throughout mind in the fingers. But such argument proves nothing at all; for it might happen that, in order that there should be in the first place that feeling, which we experience of pain in the fingers, there were required the presence of the mind in the fingers, without which it would be impossible that an idea of the pain could be excited in the first place ; but, once this idea had been formed, it might be possible that it could once more be excited, without the presence of the mind in the fingers, by the motions of the nerves, which had been conjoined with a motion of the fibres of the finger when the pain was first felt. Besides, it still remains to be decided whether any impulse of a present mind is required for nutrition, or whether this can be obtained wholly without any operation of the mind, by means of a mere mechanism alone.

537. All these things show fully that nothing certain can be stated with regard to the seat of mind from a due consideration of phenomena; nor that its diffusion throughout any great part of the body, or even throughout the whole body, is exclude. But if it should extendet throughout a great part, or even the whole, of the body, that also would fit in excellently with my Theory. For, by means of such virtual extension as we discussed in Art. 83, the mind might exist in the whole of the space containing all the points which form that part of the body, or that form the whole body. With this idea, in my Theory, the mind will differ still more from matter; for the simple elements of matter cannot exist except in single points of space at single instants of time, each to each, while the mind canalso be one-fold, yet exist at one the same time in an infinite number of points of space, conjoining with a single instant of time a continuous series of points of space; to thewhole of this series it will at one the same time be present owing to the virtual extension it possesses; just as God also, by means of His own infinite Immensity, is present in an infinite number of points of space (He indeed in His entirety in every single one), whether they are occupied by matter, or whether they are empty.

538. These things indeed relate to the seat of the mind; but I think there should be added here in the last place, concerning all the laws governing its conjuction withi the body, that which is in conformity with the observations that I made in Art. 74 Art. namely, that motion can never be produced by the mind in a point of matter, without producing an equal motion in some other point in the opposite direction. Whence it comes about that neither the necessary nor the free motions of matter produced by our minds can disturb the equality of action reaction, the conservation of the same state of the centre of gravity, the conservation of the same quantity of motion in the Universe, reckoned in the same direction.

539. So much for the mind ; now, as regards the Divine Founder of Nature Himself, there shines forth very clearly in my Theory, not only the necessity of admitting His existence in every way, but also His excellent infinite Power, Wisdom, Foresight; which demand from us the most humble veneration, along with a grateful heart, loving affection. The truly groundless dreams of those, who think that the Universe could have been founded either by some fortuitous chance or some necessity of fate, or that it existed of itself from all eternity dependent on necessary laws of its own, all these must altogether come to nothing.

540. Now first of all, the argument that it is due to chance is as follows. The combinations of a finite number of terms are finite in number; but the combinations throughout the whole of infinite eternity must have been infinite in number, even if we assume that what is understood by the name of combinations is the whole series pertaining so many thousands of years. Hence, in a fortuitous agitation of the atoms, if all cases bound to recur an infinite number of times in turn. Thus, the probability of the recurrence of this individual combination, which we have, is infinitely more probable, in any finite number of succeeding returns by mere chance, than of its non-recurrence. Here, first of all, they err in the fact that they consider that there is anything that is in itself truly fortuitous; for, all things have definite causes in Nature, from which they arise; therefore some things are called by us fortuitous, simply because we are ignorant of the causes by which their existence is determined.

541. But, leaving that out of account, it is quite false to say that the number of combinations from a finite number of terms is finite, if all things that are necessary to the constitution of the Universe are considered. The number of combinations is indeed finite, if by the term combination there is implied merely a certain order, in which some of the terms follow the others. I readily acknowledge this much; that, if all the letters that go to form a poem of Virgil are shaken haphazard in a bag, then taken out of It, all the letters are set in order, one after the other, this operation is carried on indefinitely, that combination which formed the poem of Virgil will return after a number of times, if this number is greater than some definite number. But, for the constitution of the Universe, we have first of all the arrangement of the points of matter, in a space that extends in length, breadth depth; further, there are an infinite number of straight lines m any one plane, an infinite number of planes in space, for any straight line in any plane there are an infinite number of classes of curves, which will start from a given point in the same direction as the straight line; in every one of these classes there are infinitely more which do not pass through a given number of points. Hence, when a curve has to be selected which shall pass through all points of matter, we now have an infinity of at least the third order. Besides, after any curve has been chosen, the distance of each point from the one next to it can be varied indefinitely; hence the number of possible arrangements for any one point of matter, while the rest remain fixed is infinite. Therefore it follows that the number derived from the possible changes m all of these things is infinite, of the order determined by the number of points increased at least three times. Again, the velocity which any point has at a given time can be varied indefinitel; the direction of motion can be varied to an infinity of the second order, on account of the infinity of directions in the same plane the infinity of planes in space. Hence, since the constitution of the Universe, the series of consequent phenomena, depend on the velocity the direction of motion; the number, which expresses the degree of infinity to which the number of different cases mounts upmust be multiplied three times by the number of points of matter.

542. Therefore the number of cases is not finite, but infinite of the order expressed The order of the by the fourth powerof the number of points increased threefold at least; that is so, even if there is a definite curve of forces which also can be varied in an infinity of ways. Hence the number of relative combinations necessary to the formation of the Universe is not finite for any given instant of tim; but it is infinite, of an exceedingly high order with the respect to an infinity of the kind to which belongs the infinity of the number of points of space in any straight line, which is conceived to be produced to infinity in both directions. To this infinity the infinity of the instants in the whole of eternity past present is analogous; for time has but one dimension. Hence, thenumberofcombinationsisinfiniteofanorder that is immensely higher than the order of the Infinity of instants of time; thus, not only does it follow that not all the combinations are not bound to return an infinite number of times, but the ratio even of those that do not return is infinite, of a very high order, namely that which is expressed by the fourth power of the number of points increased twofold at least, or threefold at least if we choose to vary the laws of forces. Hence, the arguments of this sort that are brought forward are futile worthless.

543. Moreover from this it also follows that, in this immense number of combinations, there will be, for any kind, infinitely more irregular combinations, such as represent indefinite chaos a mass of points flying about haphazard, than there are of those that exhibit the combinations of the Universe, which follow definite everlasting laws. For instance, in order to form particles which continually maintain their form, there is required their grouping together in those points in which there are limit-points; of these the number must be infinitely less than the number of points situated without them. For the intersections of the curve with the axis must take place in certain points; between these points there must lie continuous segments of the axis, having on them an infinite number of points of space. Hence, unless there were One to select, from among all the combinations that are equally possible in themselves, one of the regular combinations, it would be infinitely more probable, the infinity being of a very high order, that there would happen an irregular series of combinations chaos, rather than one that was regular, such an Universe as we see wonder at. Then, to overcome definitely this infinite improbability, there would be required the infinite power of a Supreme Founder selecting one from among those infinite combinations.

544. Nor can the argument be raised that even man, when he fashions a statue, with but a finite force selects that individual form which he gives to it, from among an infinite numeber which are possible. For, first of all, the man does not select that individual form; he determines in a very confused way a certain shape, that individual form aries from the law of Nature, from that individual constrution of the Universe which the Infinite Founder of Nature, overcoming the infinite lack of detemination, has determined; through which, by an act of his will, arise those definite motions in the arms of the man, from these the motions of his tools. Moreover, in general, on this account, so many philosophers have thrown back individual determination, a determination for all those stages to which the knowledge of a determining created thing cannot attain, upon a God endowed with an infinite power of knowing distinguishing, such as is necessary for the task of determining one individual case from among an infinite number pertaining to the same class. For the knowledge of a created mind can only be extended to perceiving distinctly a finite number of different stages. But, unless there is someone to determine it, one individual cannot of itself, or through fortuitous happening, possibly come forth in preference to others, from among an infinite number of cases, let alone from an infinity of infinitely such a high degree.

545. No more can it be said that this very regularity is necessary, everlasting, self sustained, any one case following the one next before it determined by it, by a law of forces that is intrinsic necessary to those individual points to no others. For against this really worthless subterfuge there are very many arguments that can be brought forward. First of all, it is very difficult to see how a man can seriously persuade himself that one particular law of forces, which one particular point has with regard to another particular point, should be possible necessary, so that, for instance, at one particular distance the points should attract one another rather than repel one another, attract one another with an attraction that is so much greater than that with which they attract others. In truth, there is apparently no connection between so great a distance so great a force of such a sort, that there could not be any other in the circumstances; that the will of a Being having infinite determinative power should not select one in particular rather than another for these points; or should not substitute, for these points that from their very nature, if you like to say so, require the first, other points that also from their nature require that other connection.

546. Besides, the infinite the infinitely small, self-determined such of themselves, is impossible in created things ; as I proved concerning the infinite in extension in several places, with more than one proof, for instance, in the dissertation De Natura usu infinitorum, infinite parvorum, in a dissertation added to my Sectionum Conicarum Elementa, Elem. Vol. 3. It therefore follows that the number of points of matter is finite; or at least, even in the commonly accepted opinion, the mass of existing matter is finite; this must occupy finite space cannot extend indefinitely. Now, there is truly no possible reason why there should be this finite number of points, or this quantity of matter in Nature, rather than that; except the will of a Being possessed of infinite determinative power. No one in his right senses will easily persuade himself seriously that there is any necessity for existence in any one number of points, rather than m any other.

547. In addition, if the Universe had gone on with these laws from eternity, then already there would have been eternal motions, straight lines described by the several points would already have been produced to infinity. For they do not re enter themselves, except by the will of a Being who overcomes the infinite improbability; since I have proved above in several places that it is infinitely more improbable that any point should return at some time to the same place as it had occupied at some other instant, than that no point should ever return. Moreover, I have proved that infinity in extension is quite impossible, as I have already observed; this impossibility must pertain to every kind of lines that have been produced indefinitely. Anyhow, the motion can be continued indefinitely throughout future eternity; for, if it commenced at any one instant there never would be an instant of time, in which there has already been the existence of an infinite line; but otherwise, if it has already existed throughout past eternity. However, in this connection, I do not think that future eternity is quite analogous with past eternity; so that this indefinite of the future is not really the same thing as an infinite of the past. But if there has not been an infinite line (absolute rest is still more infinitely improbable than a return for a single instant to the same point of space, eternal rest is even more improbable still), then it certainly follows that matter cannot have had eternal motion, nor can it have existed from eternity. For, it could not have existed without both rest motion; thus, there was altogether a need for creation, a Creator, therefore He would have an infinite effective power, so that He could create all matter, an infinite determinative force; so that, out of all the possible instants, infinite in number, in the whole of eternity indefinitely prolonged in either direction, He could choose of His Own untrammelled will that particular instant in which to create matter; out of all the infinite number of possible states, this to such a high degree of infinity, He could select that one particular state, which involves one of those curves passing through all the points taken in a certain order; in it could choose tho se determinate distances, the determinate velocities directions of the motions.

548. But, leaving all these things out of the question, there is a very strong argument in any Theory, derived also from a necessity for determination; but especially strong in my Theory, where all phenomena depend on a curve of forces, the force of inertia. Thus, although matter may be assumed to be of such a nature as to have a necessary essentialforce of inertia a law of active forces; yet, in order that at any subsequent time it may have the determinate state, which it actually has, it must be determined to that state, from the state just preceding; if thia preceding state had been different, the subsequent state woul also have been different. For a stone, which at a subsequent instant is on the earth, would not have been there at the instant, if at the instant immediatrly preceding it had been on the Moon.Hence the state which occurs at the subsequent instant, neither of itself, nor from matter, nor from any material entity then existing, has any determination to exist; the properties, which matter has unvarying, contain of themselves indifference nor do theyleadtoanydetermination.The determination, then, which that state has to exist, is derived from the state preceding it. Further, a preceding state cannot determine the one which follows it, except in so far as it itself has existed determinately. Moreover, this preceding state also has no determination in itself to exist, but derives it from one that precedes it. Consequently, we have as yet nothing in this, considered by itself, yielding determination to exist for that last state. What has been said with regard to this second state, is to be said alsoabout the third preceding state; this must receive its determination from a fourth, so in it self has no determination for its own existence, nor on that account has it any for the existence of the last state. Now, going on indefinitely in the same manner, we have an infinite series of states, in each of which we have absolutely nothing for the purpose of determining the existence of the last state. Moreover, the sum of all these nothings, no matter how infinite the number of them, is nothing also. For, it has been long ago made clear that Guide Grandi, although a very eminent geometer, enunciated a fallacy when, from an expression of a parallel series derived by division of 1 by (1+ 1), he deduced that the sum of an infinite number of zeros was really equal to 1/2. Therefore, that series of staseacannot detenine the exstence of any particular one of its terms, so neither can the whole of it exist determinately, unless it be determinad by a Being situated without itself.

549. I have employed this argument for many years past, I have communicated it to several others; it does not differ from the usual argument amployed, which denies possibility of an infinite series of contingents without on outside Being giving existence to the whole series, except in the detail that the matter is altered from a contingence to a determination, from a lack of determination of the existence of any thing in itself the question is transferred to a lack of determination for the existence of one determined state assumed as the last of the series. But my argument is superior to the usual one, in that it cannot be evaded by saying that there is in the whole series a determination to the series as a whole; since for any term there is a determination within the same series, namely onederivablefromtheprecedingterm. By my reduction to a force determining existence of the last term throughout the whole series, the result is a series of zeros with regard to this last term, the sum of these is still zero.

550. Now, the Being external to the series, which chooses this series in to all others of the preference to all infinite number in the same class, must have infinite determinative elective force, in order that He may select this one out of an infinite number. Also Hemust have knowledge wisdom, in order to select this regular series from among theirregular series; for, if He had acted without knowledge selection, it would have beeninfinitely more probable that there would have been a determination by Him of one ofthe irregular series, than of one of the regular series, such as the one in question. Forthe ratio of the number of irregular series to the number of regular serie? is infinite, that too of a very high order; thus, the excess of the probability in favour of knowledge, wisdom, arbitrary selection is infinitely greater than the probability in favour of blindchoice, fatalism. necessity; this therefore leads to a certainty.

551. Here also it is to be observed that for any individual state corresponding to any given instant of time, much more tor any particular series corresponding to a given continuous time, the the improbability of a self-determined existence is infinite; we ought to be certain of its non existence, unless it were determined by an infinite determinator, we had evidence of the determination. Thus, if it an urn there are a hundred one names, it it a question with regard to one determined name, whether it has been drawn from the urn, the improbability is a hundredfold to the contrary; if there were a thousand one names, a thousandfold; if the number of names is infinite, the improbability will be infinite; this passes into a certainty. But if anyone should have seen the drawing give us information, then the whole of the improbability would immediately be destroyed. Again, in this example, the particular determination by a created agent will not be from among an infinite number of possibles,except on account of laws already determined in Nature by an infinite Determinator and from the determination to the individual by the same power; as I said, a little earlier, when speaking of the selection of a particular form for a statue.

552. Now, if anyone will consider a little more carefully even the few things I have mentioned a necessary in the arrangement of the points for the formation of the different kinds of particles, which different bodies exhibit, he must perceive how great the wisdom power must needs be, to comprehend, select establish all these things. What then, when he considers how great an indeterminateness in problems of very high degree occurs through the infinite numeber of possible combinations; how great the knowledge would have to be to select those of them especially, which were necessary to yield this series of phenomena so far connected with one another? Let him consider what properties the single substance called light must exhibit, such that it is propagated without collision, that it has different refrangibilities for different colours, different intervals between its fits, that it should excite heat, fiery fermentations. At the same time the texture ofbodies the thickness of plates had to be made suitable for the giving forth of those kinds of rays especially, which were to exhibit determinate colours, without sacrificing other alterations and trans- formations ; the arrangement of parts of the eyes, so that an image is depicted at the back propagated to the brain ; at the same time place should be given to nutrition, thou- sands of other things of the same sort to be settled. What the properties of the single substance called. air, which at one the same time is suitable for sound, for breathing, even for the nutrition of animals, for the preservation during the night of the heat received during the day, for holding rain-clouds, innumerable other uses. What those of gravity, through which the motions of the planets comets go on unchanged, through which all things became compacted united together within their spheres, through which each sea is contained within its own bounds, rivers flow, the rain falls upon the earth irrigates it, fertilizes it, houses stand up owing to their own mass, the oscillations of pendulum syield the measure of time. Consider if gravity were taken away suddenly, what would become of our walking, of the arrangement of our viscera, of the air itself, which would flyoff in all directions through its own elasticity. A man could pick up another from the Earth, impel him with ever so slight a force, or even but blow upon him with his breath, drive him from intercourse with all humanity away to infinity, nevermore to return throughout all eternity.

553. But why do I enumerate these separate things? Consider how much geometry was needed to discover those combinations which were to display to us so many organic bodies, produce so many trees flowers, supply so many instruments of life to living brutes men. For the formation of a single leaf, how great was the need for knowledge foresight, in order that all those motions, lasting for so many ages, so closely connected with all other motions, should so bring together those particular particles of matter, that at length, at a certain determinate time, they should produce that leaf with that determinate curvature. What is this in comparison with those things to which none of our senses can penetrate, things that lie hidden far away beyond the power of telescopes, too small for the microscope? What of those which we can never understand no matter how hard we think about them, of which we can never attain not even the slightest idea; concerning which therefore, to use a phrase I have elsewhere employed to express something of the same sort, of which I say: - "We do not know the very fact of our ignorance." Undoubtedly he alone can be ignorant of the immeasurable power, wisdom foresight of the Divine Creator, far surpassing all comprehension of the human intellect, whose mind is altogether blind, or who tears out his eyes, dulls every mental power, who shuts his ears to Nature, so that he shall not hear her as she proclaims in accents loud on every side, or rather (for to shut them is not enough) cuts away, tears up destroys, hurls far from him the cochlea the tympanum anything else that helps him to hear.

554. But, in this great wisdom of selection universal foresight on the part of the Supreme Founder, the power of carryng it out, there is still another thing for us to consider; namely, how much proceeds from it to meet the needs of us, who are all under care of Hin Who sees all things, has imposed on Himself the accomplishment of all for all those purposes; Who has smoothed the path of our existence with them all, from the commencement of the Universe has chosen us in preference to an infinite number of other human beings that might have existed; Who has planned all the motions necessary for the formation of the organs we employ, besides all the many things that should conduce towards the protection preservation of this life, to its many conveniences, nay, even to its pleasures. For, it cannot be but a matter of the firmest belief, not only that the Author of Nature saw all these things with a single intuition, but also that He had settled in his mind all those purposes, to which the means that we see employed conduce.

555. I do not indeed agree with the followers of Leibniz, or with any of the upholders of Optimism, who consider that this Univers, in which we live of which we are part, is the most perfect of all; who thus make God determined by His own nature for the creation of that which is the most in that order which is the most perfect. In truth, I think that such a thing would be impossible; for, I recognize, in any kind of possibles, a series of finites only, although prolonged to infinity, as I explained in Art. 90 in this series, just as in the case of the distances between two points, there is no greatest or least, here also there is no case of greatest or of least perfection ; but, for any finite perfection, however great or small, there is another perfection that is greater or smaller. Hence it comes about that, whatever the Author of Nature should select, He would have to omit some that were of greater perfection. But, neither is it an argument against His power, that He cannot create the best or the greatest; nor similarly is it an argument against His power that, whatever He could create, He could not create it as a whole at one the same time. For, it would come to this, that He would put Himself in the position where He could create nothing better, nothing greater, or absolutely nothing else. Similarly, it is no argument against His infinite wisdom goodness, that He did not select the best, when there is no best.

556. On the other hand, that determination for the best takes away altogether the freedom of God, contingency of all things; for, those things which exist become necessary, those that do not are impossible. Besides, on that hypothesis, we should be under some sort of obligation to ourselves, not to Him, for the fact that we exist. For how was it possible that a thing should not exist, which had a powerful reason for its existence; for, when the Author of Nature saw this reason, He could not fail to follow it, nor indeed could He fail to see it? How could a thing exist which had a like need for non- existence? For what should we have to thank Him, if He had created us for the simple reason that in us He found a greater merit than in those whom He omitted, if He was necessarily determined by His own nature, driven by it to submit to our mere intrinsic essential overpowering merit? We must mark the distinction between the two dictums: (1) this thing is better than that, (2) it would be better to create this thing than to create that. There is a possibility of the first in all cases, but never any of the second. It is an equally good thing to create or not to create anything whatever, which has any physical goodness, however much greater or less than anything else which has been omitted. The exercise of Divine freedom alone is infinitely more perfect than any perfection created; the latter can therefore offer no determinative merit to the freedom of God in favour of its own creation.

557. With this infinite Divine liberty is bound up all that relates to wisdom; for, God, to those purposes which he of His own unfettered will had designed, was always bound to select suitable means, such as would not allow these purposes to be frustrated. Further, He has selected these means for the most part suitable for our welfare, whilst he founded the whole of Nature; this demands from us a remembrance of His favours a thankful heart, nay, even a love that shall correspond to such a great beneficence together with a mighty wonder admiration, as every one will see.

558. It now remains but to mention that there is no man of sound mind who could possibly doubt that One, Who has shown such great foresight in the arrangement of Nature, such great beneficence towards us in selecting us, in looking after both our needs our comforts, would not also wish to accomplish this also; namely that, since our mind is so weak dull that it can scarcely of itself arrive at any sort of knowledge about Him, He would have wished to present Himself to us through some kind of revelation much more fully to be known, honoured loved. This being done, we should indeed quite easily perceive which was the only true one, from amongst so many of those absurdities falsely brought forward as revelations. But such things as this already exceed the scope of a Natural Philosophy, of which in this work I have explained my Theory, from which I have finally gathered such ripe solid fruit.

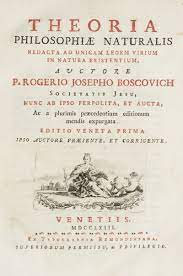

R. Boscovich, Theory of Natural Philosophy (1763), ed. by J.M. Child, Latin-English edition (Chicago - London: Open cour Publishing Company, 1922), pp. 373-391.